App Streamlines Emergency Communication in Spokane County, Wash.

(TNS) — Thousands of phones across Spokane County buzzed on Friday, Aug. 18.

Then they buzzed again. And again. And again.

The Spokane Regional Emergency Communications (SREC) center sent out dozens of evacuation alerts for the Gray and Oregon Road fires. The problem with evacuation alerts has always been that they don’t reach as many people as local leaders would like.

Spokane County uses an app called CodeRed, which requires users to opt in for Level 1 (get ready) and Level 2 (get set) alerts before switching to the national Wireless Emergency Alerts system to force notifications to most people’s cell phones.

Some older phones might not even get those more pressing alerts. Only about 6% of people in Spokane County are signed up for Code Red, said Chandra Fox, Deputy Director of Spokane County Emergency Management.

To help solve this problem, a California software developer, John Mills, created WatchDuty, a new app that uses radio traffic to post real-time updates on wildfires and evacuation zones.

Use of the app exploded in Spokane County during the late-summer wildfires, with thousands downloading the app in the first day of the fires, Mills said.

How evacuations work

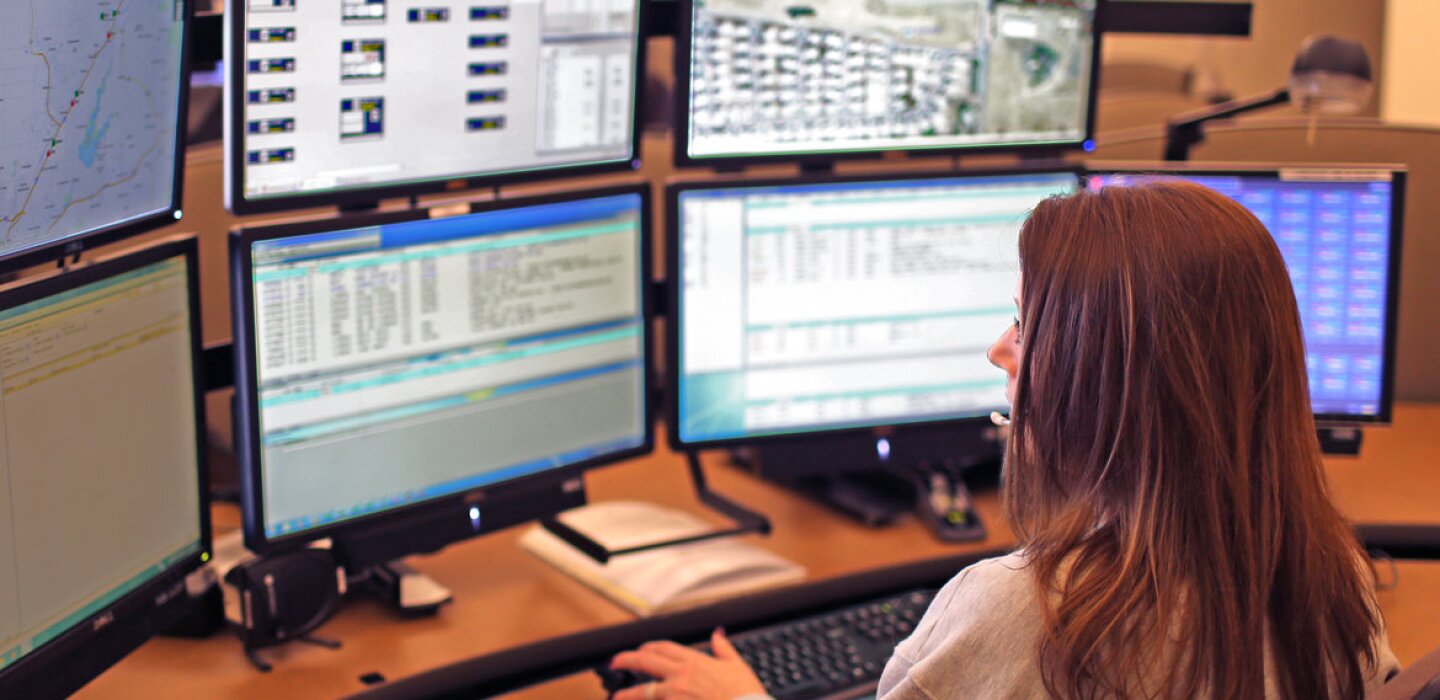

Cassidy Haas, fire dispatch supervisor at SREC, is responsible for drawing evacuation maps when a wildfire starts to spread. Fire officials on the ground determine a general evacuation zone. Then Haas examines it and often expands the evacuation zone with boundaries that make logistical sense for both residents and firefighters.

On the ground, it can be hard to tell that there’s a section of a neighborhood beyond a certain road or that everyone from one neighborhood, like around Silver Lake, only has one exit. Those are things Haas would catch as she draws evacuation boundaries.

Then she sends out the alert in CodeRed. The county’s official evacuation notices have been isolated to the CodeRed system, with no way to get the data out of the application.

“It doesn’t talk to anything else in our fire world,” Haas said.

So, after sending out the alert, she redrew the map boundaries in the dispatch system used by fire dispatch. Law enforcement dispatchers use a different system, and boundaries had to be drawn there separately.

Then, Haas would screenshot the map in the dispatch system and send it to a list of local agencies that posted them to their social media. Often, the maps would get repeatedly screenshotted, losing their clarity with each iteration.

The original screenshot itself lacked detail, though, said Joe Sacco, who does GIS mapping for Spokane Regional Emergency Communications center. The dispatch system often didn’t include road names or basic information that is visible on consumer maps.

Sacco watched Haas and her team of fire dispatchers deal with all these problems before and decided he had to fix it.

He created a patch that allows Haas to send a CodeRed alert within the dispatch system, and without all that copying and pasting she previously had to do.

“It cuts it in half,” Haas said of the time it takes to send out an alert.

The 10 minutes she saves not only get the alert to the public faster, but allow Haas to return her focus to moving around resources to help fight the fire.

After months of refining the software, the Gray and Oregon Road fires were the first big test for the patch, Sacco said.

Sacco’s patch also allowed the maps to automatically overlay onto dispatchers’ and 911 call-takers’ screens, allowing them to search an address to see if it was in the evacuation zone.

While it was a huge problem to solve internally, the Gray and Oregon Road fires made it clear people needed more information.

“Once these fires hit, it became apparent that we just had to have something more than the alerting system and the Facebooking and the social media posts and whatever,” Sacco said. “We’re not enough to get the word out there.”

Solving a problem, reaching the public

A few days into the fire, many people desperate for information had downloaded WatchDuty, something Mills wished he had when he was dealing with wildfires in his own backyard.

WatchDuty was created after Mills had to evacuate his California home and struggled to find reliable information.

“I realized someone had to solve this problem,” he said.

A tech executive, Mills began getting involved with his local Firewise community, met with government officials and local organizations, and learned they, too, struggled to find “free, honest, clear communication” about wildfires.

WatchDuty monitors other programs like Pulsepoint or InciWeb to get notice of a fire through an internal piece of software that allows the app to “listen to everything at once.”

Then WatchDuty’s reporters in that area will turn on their radios and begin listening to what firefighters are saying on the ground and post updates.

They try to be fast, but also only post verified information, typically using dispatcher channels where they can hear firefighters talking back and forth.

“Just because we’re faster than you, doesn’t mean we’re hasty,” Mills said.

Mistakes do happen, though, like when WatchDuty posted an email from Eastern Washington University Police saying Cheney was under evacuation orders. The email was from an official source, but inaccurate. WatchDuty retracted the post and clarified evacuation zones a short time later.

Still, evacuation zone maps were not as clear or useful as both Mills and Sacco thought they could be.

On day five of the fires, Sacco was given permission to turn on a beta version of his internal application for public use.

The map allowed users to search any address to see if it fell in the evacuation zone.

Sacco reached out to WatchDuty, which posted the map.

Of the 20,000 hits the application got, the majority were from WatchDuty or people searching the county’s own website, not from social media.

“We spend more time doing this thing (CODE Red) that doesn’t reach anybody than anything else,” Sacco said. “And we don’t spend any time on tools that reach people or make it easier for our own staff or our emergency responders to do their job.”

In the future, the map is expected to repeat 911 calls of people asking if they or a friend or family member is in the evacuation zone, Haas said. Often, people will call back multiple times looking for updates. The changes would steer those repeat callers to the online map, saving precious resources.

For WatchDuty, working with local governments like they’ve done in Spokane is a huge part of their goal to get accurate reliable information out quickly.

“We’re happy to be the place where humans interface with this government information,” Mills said.

©2023 The Spokesman-Review (Spokane, Wash.). Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Average Rating